MEMORIES OF MILLENNIUMS PAST WRITTEN IN STONE LOST WORLDS: ALABAMA'S ANCIENT LIFE AND LANDSCAPES

By THOMAS SPENCER

Birmingham News

staff writer

December 27, 2000

Trace the slanting rock layers of the Elton B. Stephens Expressway cutthrough skyward, far into the distant past, and imagine the mountain that might have stood here 300 million years ago, part of a chain of mountains as tall as the Alps.

By THOMAS SPENCER

Birmingham News

staff writer

December 27, 2000

Trace the slanting rock layers of the Elton B. Stephens Expressway cutthrough skyward, far into the distant past, and imagine the mountain that might have stood here 300 million years ago, part of a chain of mountains as tall as the Alps.

Today's downtown skyscrapers sit on rock layers that would have been buried two miles beneath that mountain's peak.

Picture ocean waves crashing against a shoreline forested by tropical jungle near present-day Prattville 80 million years ago. In the sky above, giant flying reptiles, pterosaurs, glide over the seas that covered today's cotton fields and Capitol dome.

Look at the black coal dug from West Alabama mines and see the remains of a prehistoric tropical swamp, crawling with huge amphibians, giant cockroaches and dragonflies with 3-foot wingspans.

A new book, Lost Worlds in Alabama's Rocks: A Guide to the State's Ancient Life and Landscapes, recounts the story written in the state's rocks: coral reefs near Cullman, Georgia volcanoes raining ash on Valley Head, triceratops tromping around Tuscaloosa, whales in Washington County, woolly mammoths near Moulton.

When the book's author, Jim Lacefield, drives Alabama's highways, he can visualize more than 500 million years of change. A seabed rumples up like a rug to form a towering mountain range. Those mountains, bit-by-bit, destroyed by time and the Lost Worlds, page 6A 1A elements and carried down streams to the sea. Oceans rise, waters recede.

As the landscape and climate have changed through the eons, the living things that have made their home in this land have changed as well.

Revealed in road cuts, quarries and the rocks in stream beds, it's a chronicle much more ancient and lasting than in any library or on any computer disk.

"These are things we all pass by every day," Lacefield said. "Once you gain a little insight into what these rocks indicate about ancient environments, climates and landscapes, you can never look at them the same way."

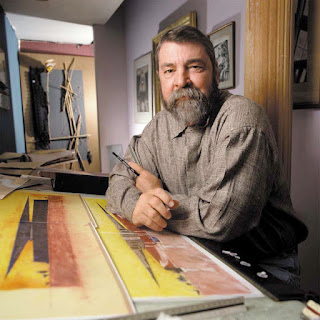

Lacefield, now an adjunct professor of biology and Earth sciences at the University of North Alabama, taught science for a number of years in public schools in North Alabama. A biologist by training, he decided to return to the University of Alabama to get a doctorate in science education and to broaden his background. Paleobiology On the road to that degree, he became interested in paleobiology, a hybrid discipline that examines fossil evidence of ancient life and traces the connections to today's plants and animals.

As a teacher, he'd had textbooks that dealt with those subjects, but the examples and evidence cited were always from elsewhere. The more he studied, the more he realized the case for the evolution of the Earth and the plants and animals living on it was all around him in Alabama landscapes.

"The story here is just as good as anywhere else," Lacefield said.

So he has turned work he did for his doctoral dissertation into a book. Published by the Alabama Geological Society, the book has 300 color photos, plus paleo-maps and fossil charts, detailing and illustrating the record of more than 500 million years of change in Alabama's environments and living communities.

The book presents current scientific ideas and new evidence about how the Earth, and particularly the land that would become Alabama, has been shaped through the ages. Since the 1960s, with the development and refinement of the theory of plate tectonics, the field of geology has undergone a revolution.

According to the theory, the uppermost layers of the Earth - the continents and the ocean floor - are made up of large plates that "float" on softer, more fluid rock beneath. Over the course of millions of years, these plates have collided, driving up mountains, and ripped apart, forming ocean basins.

In their movements, the continents have drifted across the face of the globe, from the equator to the poles.

As the theory has been applied to current geologic events and is bolstered by evidence from the fossil record, it has helped explain many hitherto mysterious aspects of the Earth and its processes.

For instance, why do several layers of rock and fossils deep beneath southeastern Alabama match up better with African geology than North American?

Because evidence indicates that about 250 million years ago the Earth's continents were joined together in a supercontinent we now call Pangaea. When what is now Africa slowly tore away from North America, about 200 million years ago, it left a sizable chunk of itself behind.

The land deep beneath Dothan was once a part of Africa, near modern-day Senegal.

Using the clues found in local rocks, Lacefield's book follows Alabama's journey through the past half-billion years. "This book was written to help Alabamians understand modern geology. The age, the changes, the progression of living communities through time, those are written in the rocks we see," Lacefield said. South of equator It's a story that begins 500 million years ago on the bottom of warm shallow seas when, in successive waves, the layers of limestone and iron ore that underlie the Birmingham area were deposited.

Continuing, it finds Alabama 300 million years ago, located well south of the equator, feeling the impact of North America's collision with Africa as those earlier layers rumpled up like a rug to form the Appalachian Mountains. With the mountains to the east starting to be thrust upward during the Pennsylva nian Period, much of northern Alabama was a broad coastal plain fed by a great river that ran down the western flank of the young mountains.

The remains of the lush tropical forests that grew in those coastal swamps were buried under sand and mud to become a thick blanket of organic matter, which eventually formed coal deposits.

Concurrently, Lacefield traces the progression of the animal life that inhabited the land and the seas. In 500-million-year-old Alabama limestone are fossils of primitive sea creatures, trilobites, that would have inhabited the warm seas that then covered the Birmingham area. In 300-million-year-old shale and sandstone from Walker County are footprints left by amphibians that made their homes in Coal Age swamps. Giant crocodiles Meat-eating dinosaurs roamed a coastal plain arcing from Auburn to Tuscaloosa 100 million years ago. Their bones are found along with fossil remains of their landscape: tropical figs, palms and cinnamon trees.

The seas covering South Alabama at the time swam with creatures like the 35-foot-long mosasaurs, a carnivorous marine lizard; turtles as large as 12 feet in diameter; and sea-going crocodiles up to 40 feet long.

More recent fossils, dating from 2 million up until 10,000 years ago, during the last Ice Age, show the state was home to woolly mammoths, camels and giant ground sloths. With much of the Earth's water locked up in the polar ice caps, sea levels were much lower at that time.

Alabama's coastline would have been 60 miles south of modern-day Gulf Shores.

In that colder climate, forests resembling those in Canada now covered North Alabama. Birch and hemlock trees descended from that cold forest remain today in the damp, cool canyons of the Bankhead National Forest.

Lacefield's book is something of a mix: a field guide for fossil hunters, a primer on the Alabama rock formations and how to recognize them along the highways, and a prologue to the continuing story of the land of Alabama as it evolves through time.

"Every time we have a rain and we see a little cloudiness in the streams, that is the Earth in change. The mountains are wearing down and washing away and new land is forming from these particles along Alabama's coastline," Lacefield said. When you walk the white sand beaches of the Alabama coast, you're walking on dissolved rock, washed down from vanished mountains. If you happen upon a horseshoe crab on the beach, you might be able to imagine his Coal Age ancestors crawling on the shores of Walker County 300 million years ago.

"All these processes are continuing into the future," he said. "The timeless processes shaping the land are those same ones that we see recorded in the rocks from long ago."

Picture ocean waves crashing against a shoreline forested by tropical jungle near present-day Prattville 80 million years ago. In the sky above, giant flying reptiles, pterosaurs, glide over the seas that covered today's cotton fields and Capitol dome.

Look at the black coal dug from West Alabama mines and see the remains of a prehistoric tropical swamp, crawling with huge amphibians, giant cockroaches and dragonflies with 3-foot wingspans.

A new book, Lost Worlds in Alabama's Rocks: A Guide to the State's Ancient Life and Landscapes, recounts the story written in the state's rocks: coral reefs near Cullman, Georgia volcanoes raining ash on Valley Head, triceratops tromping around Tuscaloosa, whales in Washington County, woolly mammoths near Moulton.

When the book's author, Jim Lacefield, drives Alabama's highways, he can visualize more than 500 million years of change. A seabed rumples up like a rug to form a towering mountain range. Those mountains, bit-by-bit, destroyed by time and the Lost Worlds, page 6A 1A elements and carried down streams to the sea. Oceans rise, waters recede.

As the landscape and climate have changed through the eons, the living things that have made their home in this land have changed as well.

Revealed in road cuts, quarries and the rocks in stream beds, it's a chronicle much more ancient and lasting than in any library or on any computer disk.

"These are things we all pass by every day," Lacefield said. "Once you gain a little insight into what these rocks indicate about ancient environments, climates and landscapes, you can never look at them the same way."

Lacefield, now an adjunct professor of biology and Earth sciences at the University of North Alabama, taught science for a number of years in public schools in North Alabama. A biologist by training, he decided to return to the University of Alabama to get a doctorate in science education and to broaden his background. Paleobiology On the road to that degree, he became interested in paleobiology, a hybrid discipline that examines fossil evidence of ancient life and traces the connections to today's plants and animals.

As a teacher, he'd had textbooks that dealt with those subjects, but the examples and evidence cited were always from elsewhere. The more he studied, the more he realized the case for the evolution of the Earth and the plants and animals living on it was all around him in Alabama landscapes.

"The story here is just as good as anywhere else," Lacefield said.

So he has turned work he did for his doctoral dissertation into a book. Published by the Alabama Geological Society, the book has 300 color photos, plus paleo-maps and fossil charts, detailing and illustrating the record of more than 500 million years of change in Alabama's environments and living communities.

The book presents current scientific ideas and new evidence about how the Earth, and particularly the land that would become Alabama, has been shaped through the ages. Since the 1960s, with the development and refinement of the theory of plate tectonics, the field of geology has undergone a revolution.

According to the theory, the uppermost layers of the Earth - the continents and the ocean floor - are made up of large plates that "float" on softer, more fluid rock beneath. Over the course of millions of years, these plates have collided, driving up mountains, and ripped apart, forming ocean basins.

In their movements, the continents have drifted across the face of the globe, from the equator to the poles.

As the theory has been applied to current geologic events and is bolstered by evidence from the fossil record, it has helped explain many hitherto mysterious aspects of the Earth and its processes.

For instance, why do several layers of rock and fossils deep beneath southeastern Alabama match up better with African geology than North American?

Because evidence indicates that about 250 million years ago the Earth's continents were joined together in a supercontinent we now call Pangaea. When what is now Africa slowly tore away from North America, about 200 million years ago, it left a sizable chunk of itself behind.

The land deep beneath Dothan was once a part of Africa, near modern-day Senegal.

Using the clues found in local rocks, Lacefield's book follows Alabama's journey through the past half-billion years. "This book was written to help Alabamians understand modern geology. The age, the changes, the progression of living communities through time, those are written in the rocks we see," Lacefield said. South of equator It's a story that begins 500 million years ago on the bottom of warm shallow seas when, in successive waves, the layers of limestone and iron ore that underlie the Birmingham area were deposited.

Continuing, it finds Alabama 300 million years ago, located well south of the equator, feeling the impact of North America's collision with Africa as those earlier layers rumpled up like a rug to form the Appalachian Mountains. With the mountains to the east starting to be thrust upward during the Pennsylva nian Period, much of northern Alabama was a broad coastal plain fed by a great river that ran down the western flank of the young mountains.

The remains of the lush tropical forests that grew in those coastal swamps were buried under sand and mud to become a thick blanket of organic matter, which eventually formed coal deposits.

Concurrently, Lacefield traces the progression of the animal life that inhabited the land and the seas. In 500-million-year-old Alabama limestone are fossils of primitive sea creatures, trilobites, that would have inhabited the warm seas that then covered the Birmingham area. In 300-million-year-old shale and sandstone from Walker County are footprints left by amphibians that made their homes in Coal Age swamps. Giant crocodiles Meat-eating dinosaurs roamed a coastal plain arcing from Auburn to Tuscaloosa 100 million years ago. Their bones are found along with fossil remains of their landscape: tropical figs, palms and cinnamon trees.

The seas covering South Alabama at the time swam with creatures like the 35-foot-long mosasaurs, a carnivorous marine lizard; turtles as large as 12 feet in diameter; and sea-going crocodiles up to 40 feet long.

More recent fossils, dating from 2 million up until 10,000 years ago, during the last Ice Age, show the state was home to woolly mammoths, camels and giant ground sloths. With much of the Earth's water locked up in the polar ice caps, sea levels were much lower at that time.

Alabama's coastline would have been 60 miles south of modern-day Gulf Shores.

In that colder climate, forests resembling those in Canada now covered North Alabama. Birch and hemlock trees descended from that cold forest remain today in the damp, cool canyons of the Bankhead National Forest.

Lacefield's book is something of a mix: a field guide for fossil hunters, a primer on the Alabama rock formations and how to recognize them along the highways, and a prologue to the continuing story of the land of Alabama as it evolves through time.

"Every time we have a rain and we see a little cloudiness in the streams, that is the Earth in change. The mountains are wearing down and washing away and new land is forming from these particles along Alabama's coastline," Lacefield said. When you walk the white sand beaches of the Alabama coast, you're walking on dissolved rock, washed down from vanished mountains. If you happen upon a horseshoe crab on the beach, you might be able to imagine his Coal Age ancestors crawling on the shores of Walker County 300 million years ago.

"All these processes are continuing into the future," he said. "The timeless processes shaping the land are those same ones that we see recorded in the rocks from long ago."

Comments

Post a Comment