HABITATS WITH VISION AUBURN ARCHITECTURE NOVICES DESIGN, BUILD LOW-COST HOMES HABITAT HOUSE HAS STYLE AS WELL AS LOW COST

|

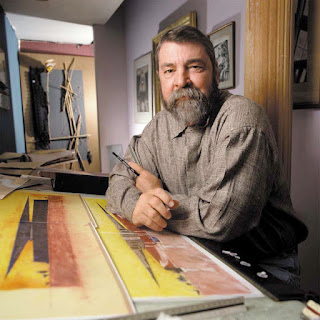

| Birmingham News Photo credit: Andreas Fuhrmann |

by THOMAS SPENCER

News staff writer

Publication Date: June 22, 2002 Page: 01-B Section: Lifestyle Edition: Volume 15 Issue 12

OPELIKA It's a match that Auburn University's late, great architecture professor Samuel "Sambo" Mockbee must be smiling about in heaven.

Take the force and determination of Habitat for Humanity, the volunteer army that since 1976 has built more than 110,000 homes for low-income families who might not otherwise be able to own a home.

Combine that with Mockbee's vision: That architectural style and know-how should extend beyond the rich and serve the poor, the vision that sustains the Rural Studio, Auburn's outpost in Hale County, where students design and build shelter for some of the Black Belt's poorest residents.

As Mockbee, who last year died after a long battle with leukemia, put it: "The goal is not only to have a warm, dry house, but to have a warm, dry house with a spirit to it. What we build are shelters for the soul as well as homes for bodies."

And there is a spirit spinning round the ceiling fan hung from heights of the vaulted ceiling of Nancy Johnson's screened porch this sweet summer evening in Opelika. She and her daughter, Monquetta, 17, share the porch with three of the Auburn architecture students who designed and built her new Habitat-financed home.

Johnson's home is the product of a collaboration among Alabama affiliates of Habitat, the nonprofit group DesignAlabama, and Auburn's School of Architecture, Design and Construction. Helped along with a $10,000 donation from Home Depot, the students have built a prototype for future Habitat homes in Alabama, an updated and energy-efficient home plan engineered to match the state's climate but also touched with Southern-accented style.

It includes taller ceilings, vents in the ceiling, larger windows and porches, among other details.

A different look Johnson, who is a pharmacy technician at East Alabama Regional Medical Center, was involved in the design process, helping steer the students toward a design that fit her needs.

"I like the high ceilings and I like that it's different from all the other Habitat houses," she said. "If you are riding by it, people wouldn't know it's a Habitat house."

On the lot behind Johnson's house sits a standard Habitat home: solid, conventional, but plain. The exterior is vinyl siding, topped with a low-pitched asphalt-shingled roof.

Habitat homes have generally been Habitat, Page 6B 1B built according to this simple design: a square functional box atop a concrete slab. The standard serves Habitat well: volunteer and often inexperienced laborers build affordable homes, which Habitat families pay for through no-interest loans.

But Habitat homes are sometimes criticized for not blending in with the existing neighborhoods and for lacking a sense of individual and localized style.

Auburn's design team was tasked with adding some indigenous style, keeping construction simple and affordable, and increasing the long-term affordability to the homeowner by cutting energy costs.

Before launching into design, David Hinson, an associate professor of architecture at Auburn, divided his 20 architecture students into teams that spent three months last fall studying areas that would be key to a successful design.

One team looked at previous collaborations between architects and Habitat to try to understand why some worked and others failed.

Sticking to mission "Habitat is not resistant to design innovation," Hinson said, "but they don't want anything to get in the way of their mission of building a lot of homes with volunteer labor."

The Auburn team was shooting for keeping costs under $38,000. When they tallied up their final costs, they'd managed to make the improvements while keeping the cost around $35,000, the average cost for Habitat homes in the region.

As it turned out, the questions of style, making the house blend in with older housing, served a dual purpose. Many of the traditional architectural elements in Southern homes were used to keep houses cooler.

During and after the postWorld War II building boom, those traditional elements were largely discarded, according to Hinson. With the advent of air conditioning and with the availability of plentiful and cheap electricity, builders didn't worry about the orientation of the house in regard to the sun, nor the shading or ventilation tricks used in older housing because it was assumed that air-conditioning and heat would regulate the indoor temperature.

But with energy prices surging, many of the older building practices are being revived in the mainstream housing market in the interest of saving energy and increasing appeal.

During the spring and the fall in Alabama, a well-designed house need not depend on airconditioning or heat. Those energy savings are particularly important to low-income residents whose utility bills consume a disproportionate share of their paychecks.

"It doesn't have to be that way for you or me or for the Habitat families," Hinson said.

"The project has been spectacular," said Karen McCauley, executive director of the Alabama Association of Habitat Affiliates.

"The talents and the time of the students to research that has been atremendous resource for us," she said.

The Alabama Habitat affiliates are launching a sponsorship campaign to raise money to build 50 houses across the state based on the Auburn design.

High-ceiling advantage

Nancy Johnson's ceilings are 9 feet tall, allowing more room for heat to rise. The living room ceiling and roof above the screened porch are vaulted, rising to a height of 15 feet.

In the heights of the living room, the students incorporated vents that open to let the heat escape. Above each of the interior doors is a transom, fashioned from a segment of shutter turned on its side and built into a frame above the door.

When the shutter is open, air can move through those vents, while the doors can remain closed to maintain privacy. There are also ceiling fans throughout the house and a whole-house fan will pull air in through the windows and send hot air up and out of the attic.

The Auburn team chose a higher grade of insulation for the attic and their choice of roofing, a white reflective metal roof, will keep the house much cooler than a black asphalt shingle roof, Hinson said.

In addition to its resistance to heat, the metal roof will last the lifetime of the house. Shingled roofs have to be replaced every 15 years.

The Auburn design uses more and bigger windows than the Habitat standard, letting in more light. That not only decreases lighting costs but also decreases cooling costs. Electric lighting is an often unrecognized but significant source of heat in a house.

While most Habitat homes are built on concrete slabs, Johnson's home has a crawl space beneath for easier access to utilities and maintenance. Plus, the elevation provides protection from termites and allows for the cooling ducts to run under the house rather than through the heat of the attic.

Taken together, Hinson said, these elements can substantially reduce the cost in energy for the homeowner over the lifetime of the house.

The Auburn house, which students built in 11 weeks working three afternoons a week, plus the occasional Saturday, can be adapted for three or four bedrooms.

Beyond the practical improvements the Auburn house makes, the house has a sense of style. The 9-foot ceilings throughout give a greater sense of space. A room-sized screened porch is integral to the design. Double doors from both the dining room and living room open onto the porch. And those rooms are joined with the kitchen in one large open space.

"The quality of living goes up in a well-designed space," said Emily McGlohn, a rising fifthyear student from Hoover.

The porch, positioned on the southwest corner of the house, provides the functional benefit of creating a well of shade from the harsh afternoon sun, but it also creates an inviting livable space, enhancing the sense of neighborhood.

"If there is activity on the porch, people are watching the street and the street becomes safer," Hinson said. "Individuals' design decisions have a collective impact on the neighborhood."

Instead of vinyl siding, Auburn students chose to use cement fiber "Hardy board." The durable board looks like wood and can be painted to suit the taste of the resident.

The Rural Studio's designand-build, community service training the students got on the project has become a trademark of Auburn's architecture training. It brings architecture out of the studio and into the real world of cost and construction, the students said.

"An experience like that has bearing on all that you do," said Paul Kardous, a fourth year student, from Charlotte.

It might mean sweat and blisters and hammer-busted thumbs, but as McGlohn said after chasing Johnson's 6-year-old daughter Marquita through the twilight, "It's the most fun. I've ever had." To learn more and to see photos of the construction, go to http:// cadc.frontpage.auburn.edu/ content/habitat/

Comments

Post a Comment